Navigating the Asia Pacific Pharmaceutical Landscape for Global Impact

The Asia Pacific region (APAC), like any large territory, encompasses a blend of well-established and early-stage economies, diverse healthcare systems, and differences in language, culture, politics, and technology adoption. APAC’s size and complexity has created new challenges and opportunities for the pharmaceutical industry as nations work together to meet the manufacturing needs for medical products.

Complexity of APAC

“I’d say almost everything about APAC is unique,” said Charlie Wakeham, Director at WakeUp to Quality in Australia and a pharmaceutical quality and compliance expert. “It’s convenient to stick a tag on the map and call it Asia Pacific, like it’s one entity, but it isn’t. It’s a vast geography, with language barriers, geographical challenges, and a sliding scale of technology adoption.”

From Japan and South Korea to Australia and New Zealand, it is indeed vast, and the range of capabilities, strengths, and challenges of the pharmaceutical industry is difficult to summarize. The particularities that exist throughout APAC significantly affect the pharmaceutical landscape and have challenged nations to meet both domestic and global needs for medical products. Efforts to address these challenges—for example, through collaborative regulatory initiatives and the adoption of technological advances—is fueling a burgeoning pharmaceutical industry.

“API [active pharmaceutical ingredient] export manufacturers from a country like South Korea are very sophisticated,” Wakeham said. “To compete in the global market and sell in places like the US, they know they have to invest in the necessary technology. At the other end of the scale are coun-tries with less automation and networked equipment.”

“The range within APAC really interests me,” said Maurice Parlane, Director at New Wayz Consulting in New Zealand and Director and Partner, CBE Pty Ltd in Australia. “The industry in some countries, like Singapore, is outwardly focused. Then there are many other economies, like Indonesia, Malay-sia, and Thailand, striving to build capacity in the local manufacturing network for domestic consumption. Vietnam has a lot of foreign investment coming in from Japan and Korea and other overseas markets. In Indonesia, big pharma companies want to have a presence because the market is so large. Korea is also a large market, but focuses more on the US market and has taken a different tack than Singapore, which attracted foreign pharma companies to build large manufacturing facilities, whereas South Korea established a biotechnology center in Osong. There are many startups there and a lot of bio-similar work in that area. It seems that they have critical mass. As you see, each country is different.”

Exploring the complexities within the region highlights the ways APAC continues to develop as an important nexus for the worldwide supply of drugs.

Industry Challenges in APAC

The pharma industry must meet the challenges that arise from the geographical and cultural constraints within APAC. Language, of course, can be a barrier to cooperation and trade. The lingua franca for many manufacturers in APAC countries is English, given their desire to supply drugs to markets in Europe and the US. This includes places like Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand. For other countries, like South Korea and Japan, there may be a more relevant second language than English.

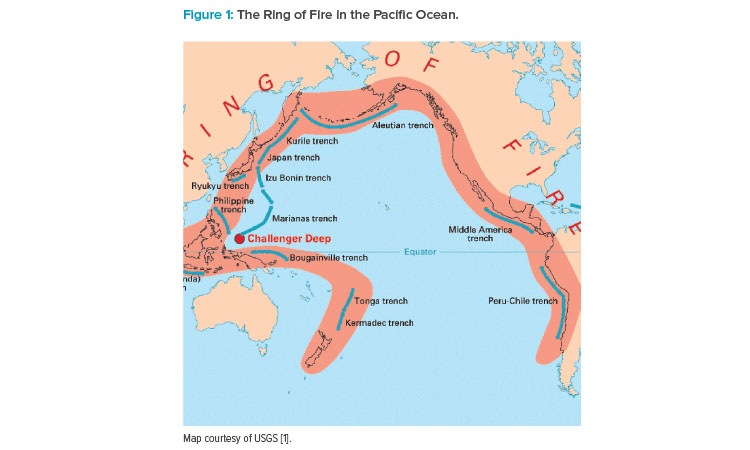

Most of APAC sits on the Ring of Fire, a band of volcanoes and tectonic activity in the Pacific Ocean that is prone to earthquakes and tsunamis (see Figure 1).

“Because of the risk of natural disasters, business continuity requires careful consideration about where to store materials off site,” Wakeham said. “In Australia, it might be enough if you’re located in Sydney to have backup data in Melbourne, but those nearer the Ring of Fire have to think bigger. This could mean choosing an offshore data center on a separate tectonic plate.”

Complex historical relationships and ongoing political tensions can adversely affect the free flow of goods and services. “Also, most countries are proud of their domestic manufacturing capabilities,” Wakeham said. “They may choose internal over external providers based on this.”

While these challenges exist for manufacturers in any industry, there are two big challenges particular to the pharmaceutical industry: the need to bridge the regulatory regimes that exist country by country and the wide range of technology adoption and capabilities. On both fronts, APAC is making significant gains.

Harmonization of Quality and Compliance

Given the large number of APAC countries involved in the industry, there has historically been a patchwork of regulations that makes it challenging for manufacturers to export to other countries in the region. Wakeham also noted that the level of knowledge and expertise varies across APAC. Fortunately, there is now a common GMP standard that most countries follow.

Alignment to PIC/s GMP Standards

The Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) is a non-binding collaboration of regulatory authorities, each of which adheres to a similar GMP inspection system, to align inspection approaches globally. Currently, there are 56 participating regulatory agencies globally. PIC/S members within APAC include the regulatory authorities of Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Although the regulatory agencies of India and China are not PIC/S members, both countries have large numbers of export manufacturers working to PIC/S GMP standards to access global markets, and China has applied for PIC/S membership.

“By providing a common standard across the region, PIC/S GMP standards are of tremendous importance within Asia Pacific and to facilitate access to the wider global market,” Wakeham said.

In addition, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which includes the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia, are signatories to a mutual recognition agreement to harmonize on PIC/S GMP irrespective of their national GMPs.2 This greatly simplifies trade between these nations. If a manufacturer has a GMP certificate from a PIC/S member regulatory agency (e.g., the Australia Therapeutic Goods Administration [TGA]), other PIC/S members may choose to accept their products without their own further inspection. Governments are promoting this because it makes them more compatible with international markets.

“While it’s a step forward, it’s not yet a perfect system,” said Bảo Nguyễn, a quality control manager in Vietnam. “Responding to regulations of coun-tries in the region can still be difficult. The level of requirements can vary greatly throughout Southeast Asia, and a Vietnamese company may encounter different regulations despite the application of the same standards. For example, although they all participate in PIC/S, the regulations in Thailand, Ma-laysia, and Indonesia are different in terms of registration dossiers. There are also some special local regulations, like Halal in Indonesia.”

Regulatory Expertise Can Be Variable

“The level of knowledge and expertise in the regulatory agencies is variable across the region,” said Wakeham, who has provided training directly to many regulatory agencies in the region, including Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, South Korea, Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam. “Some entrenched attitudes are difficult to break, such as the insistence among some regulators to keep a paper copy of an approved elec-tronic copy of a paper record.”

Parlane, who is an ISPE trainer, knows that learning about regulations and quality requires understanding the reasons for the rules. “Success is not about regurgitating a guide. It’s about learning the ‘why’ behind a rule. It’s even more important to have a culture that sees the importance of the why. Embracing PIC/S shows the industry recognizes the need to gain knowledge and the incredible growth in membership of APAC ISPE Affiliates reflects this. I see Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia being close to being able to export significant amounts of medicines.”

“There needs to be a mindset shift,” said Shanshan Liu, Technical Director, No deviation Pte Ltd, a consultancy in Singapore providing industry sup-port for commissioning, qualification, and validation, as well as engineering. “Countries are recognizing the need to put quality by design in place and use the best equipment. But what’s even more important is the systems implemented in their facilities—the quality system and procedures. The way they operate and maintain the equipment makes all the difference.”

Digitalization Is on the Horizon

“It’s only now that there’s a need for digitalization in much of APAC,” Wakeham said. “Earlier manufacturing in the region was focused on domestic or local markets and depended on low levels of automation and connectivity. As ambitions grow, so have quality standards and expectations.”

This has raised the collective regional knowledge and expectations, making the time ripe for GAMP® in APAC. GAMP, a community of practice (CoP) within ISPE, is focused on computerized systems quality and data integrity and the use of automated systems in the industry. Wakeham set up GAMP South Asia, a CoP for the region. She is currently the chair of both the GAMP Global Steering Committee and the GAMP South Asia CoP. GAMP South Asia provides a unique blend of collaboration and knowledge sharing, allowing Asian countries to tap into the education ISPE offers.

“The digital needs in Asia Pacific are unique,” Wakeham said. “APAC needs a local focus by local people because it’s not the same as making pharma-ceuticals in the US or Europe. We need that level of knowledge sharing and mutual upskilling to get the best out of computerized systems. While it’s getting better, there are still challenges with IT infrastructure. While most cities have good connectivity and bandwidth, locations with unreliable con-nectivity hinder companies from using software as a service (Saas) in the cloud for their daily operations. This can impact something as imperative as the need to transition from paper records to digital records.”

Thailand

Thailand has a vibrant biopharmaceutical industry due in part to the size of its domestic market. By revenue, oncology drugs are the most lucrative products manufactured in the country.3 Government policy has promoted affordable healthcare, leading to a shift toward generic drug manufacturing. Tax incentives attract significant foreign investment with seven of the top 10 companies in the industry being multinationals, including GSK, Pfizer, and Novartis. The government has also facilitated research and development of innovative treatments through the establishment of the Thailand Center of Excellence for Life Sciences.

The ISPE Thailand Affiliate

The Thailand Affiliate has been active for more than 20 years and has 460 members. It collaborated with industry and others in the country to become a member of PIC/S GMP in 2016. The Affiliate was an important advisor to the government initiative to develop a roadmap for manufacturing advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs).

Indonesia

Parlane noted that vaccine manufacturing is growing in Indonesia and thinks the market for innovative drugs is particularly appealing in a country that has more than 270 million people. Large pharma companies are attracted to the market but, due to government regulations, must partner with a domestic company.

“Supplying Indonesia makes sense given the size of the market and the fact that it’s an ASEAN member,” Parlane said. “While BPOM [the Indonesian regulatory agency] is PIC/S accredited, it doesn’t lead to a lot of exports. Sometimes it’s easier to import a drug into the country than it is to make it there.”

The ISPE Indonesia Affiliate

The ISPE Indonesia Affiliate is very active and has been in existence for over 20 years. They run a well-attended annual conference which includes topical GMP themes. The 2023 conference ran over

2 days with over 300 industry attendees. The theme of the conference was “Technology Innovation–Adhering to Ethical Behavior and Ensuring Patient Safety.” Outside of the conference, the affiliate is very active with events most months, often featuring international subject matter experts. Badan POM, the Indonesian GMP regulator, was one of the first APAC authorities to be PIC/S approved in 2012 and actively participates and supports the local Affiliate.

India: Pharmacy of the World

The Indian pharmaceutical industry is a major player, not only in APAC, but globally. Some estimates value it at US $50 billion and expect rapid, continuous growth, supplying as much as 20% of the world’s generic medicines and 60% of global vaccine demand.4 Indian companies received almost half of the 742 abbreviated

new drug application approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022.5

Interest in complex generics is burgeoning and has the potential to enhance long-term growth for pharmaceutical manufacturers in India. The challenges of developing successful manufacturing processes limits competition and offers a higher return on investment for companies in this sector, which includes Dr. Reddy’s, Zydus, Glenmark, Aurobindo, Torrent, Strides, Lupin, Cipla, and Sun.

Singapore

Singapore has a well-established pharmaceutical infrastructure, with manufacturers such as Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, and Amgen having set up shop and introducing innovative technologies (e.g., continuous manufacturing, Manufacturing Execution Systems, and Process Analytical Technology) to the country.

“Singapore has invested heavily in biologics and other complex, high-value products, like personalized medicines,” said Liu. “This emphasis is in both research and development and manufacturing.”

Liu noted that the strength of the industry—eight of the top 10 pharmaceutical companies operate in the country—led to the government putting greater emphasis on research. The country has invested to develop an entire system supporting advanced therapies, including pharmaceutical companies and contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs), clinicians investigating new therapies, and tertiary institutes like the Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (A*STAR) and the National University of Singapore. It also created the Advanced Cell Therapy and Research Institute (ACTRIS), a significant investment in infrastructure that aims to be a center of excellence in the region for the discovery, development, and production of cell therapies.

“Singapore is an attractive destination for talent from places like the States and Europe,” Liu said. “The politics are stable and regulatory policies are beneficial for the pharma industry. The concentration of industry provides a centralized pool of talent and resources, making it efficient for companies to plan.”

It also has a resilient supply chain, with multiple ports and good relationships with different nations and suppliers. The government developed a biomanufacturing center on the western end of Singapore. Tuas is a densely contained base for large-scale manufacturing of small molecules and traditional antibody therapies. Manufacturing facilities for Novartis, Lonza, GSK, Amgen, Abbott, Roche, MSD, and Pfizer are located there.

Success is not about regurgitating a guide. It’s about learning the “why” behind a rule. It’s even more important to have a culture that sees the importance of the why.

One domestic company is CellVec, a CDMO that develops and produces viral vectors for both clinical and commercial applications in cell and gene therapy (C>) within its GMP-certified manufacturing facility. It is located in south Singapore near a container terminal, alongside high-tech companies like Google.

“Singapore has a long history as a pharmaceutical manufacturing powerhouse, with the kind of supply infrastructure that makes it a good place to set up a CDMO like CellVec,” said Lucas Chan, Founder and Chief Scientific Officer, CellVec. “As a major trading partner to the US, Europe, and Japan, we’re easily able to import the raw materials we need to develop our cell and gene therapies.”

Establishing a GMP-accredited capability in the region is an important step toward self-sufficiency and means we can improve access to these transformative therapies within Southeast Asia and the wider region.

“Despite ongoing technological advancement in gene transfer technologies, viral vectors remain a staple and critical enabling component to both the development and commercialization of C> products, and supplies continue to be a significant bottleneck in Europe, America, and in Australia,” Chan said. “Establishing a GMP-accredited capability in the region is an important step toward self-sufficiency and means we can improve access to these transformative therapies within Southeast Asia and the wider region.” He added there are ongoing C> development efforts in many APAC countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and India, all of which require a stable supply of GMP-compliant viral vectors.

The small size of Singapore gives it the advantage of needing only one centralized regulatory agency, the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), making harmonization much simpler. Singapore, as a member of PIC/S, shares mutual recognition of GMP standards with regulators in other jurisdictions, such as Australia’s TGA. This has led to scientific collaborations within the region and beyond, including a partnership between CellVec and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Australia to provide viral vectors for the center’s clinical development pipeline of autologous cell therapies.

“Another advantage Singapore has is at the established level of regulatory standards, through Singapore’s regulatory agency, HSA. This has resulted in the international recognition of the quality of biomanufacturing in the country,” Chan said. “Establishment of these standards and practices requires a significant level of infrastructure investment from the government, and Singapore has done a lot of this over the last 20 years. Being a GMP-accredited manufacturer has enabled us to export clinical C> vectors for both the wider region and internationally.”

The ISPE Singapore Affiliate

Shanshan Liu is chair of the ISPE Asia Pacific Affiliate Council whose members include Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and India. There are local affiliates throughout APAC, including the ISPE Singapore Affiliate, which has 300 active members. Liu is President of the ISPE Singapore Affiliate. The ISPE Singapore Affiliate’s mission is to provide accessible educations to the workforce and to connect the industry. The Affiliate provides education sessions within the country and helps organize educational events in other countries in the region.

“We have really close working relationships with each other,” said Liu, who is qualified as an ISPE instructor for Commissioning and Qualification (C&Q) and ATMP modules, among other subjects. “Often two countries will collaborate on official ISPE training, so we can make the traveling of instruc-tors more efficient and share the license fee.”

The Affiliate hosts the annual ISPE Singapore Conference & Exhibition, bringing together participants from around the world to hear keynote addresses, attend workshops, and visit an exhibitor hall. Regulators from the World Health Organization, European Medicines Agency, and other agencies also offer presentations. The 2023 conference saw more than 1,500 participants attending on-site, making it the biggest conference so far.

“We offer packages to attract more people, such as C&Q training,” said Liu. “This way they can experience the technical and networking benefits of becoming members of the Singapore Affiliate.”

Malaysia

“The pharmaceutical manufacturing sector in Malaysia is primarily focused on generics,” said Zarina Noordin, Quality and GMP Consultant, and President of the ISPE Malaysia Affiliate. “Patented products from multinational companies are mostly imported. Areas of growth include vaccine production and cell and gene therapies. Medical device manufacturing is also growing, especially during the pandemic, with many players opening new factories.”

The medical device market has a projected revenue of more than US $3 billion in 2023, with cardiology devices at the forefront.6

“While the Malaysian pharmaceutical industry has a well-educated workforce, most of whom speak English, there’s a significant brain drain to neighboring countries,” Noordin said. “There’s also a lack of skilled personnel in biotech and biopharma. We see ISPE playing an important role to fill this gap with our publications, education content, and global network.”

“It is the larger companies that have the resources needed to meet GMP and market demands for new modalities,” Noordin said. “Even then, the decline in the value of the Malaysian ringgit makes it a challenge to innovate and invest in digitalization and technology to meet Annex 1 requirements.”

Two examples of large, local companies investing in biotech, digitalization, and innovative technology are Pharmaniaga Berhad and Duopharma Biotech, which have multiple sites in Malaysia and throughout the region.

The ISPE Malaysia Affiliate

This Affiliate provides education on topics such as biotech, C>s, and new advances in manufacturing, and assists smaller players in the fundamentals of GMP. There is interest in good distribution practices (GDP) training for small- to medium-sized companies, requested by the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA).

“The Malaysian pharma industry is a relatively small one,” said Noordin. “The Affiliate has a vibrant program to help develop the human capital needed in Malaysia. We provide a professional platform for industry—companies, regulators, government agencies, academics, students, and vendors—to network and learn through monthly webinars, in-person GDP and vendor seminars, social events, and the annual conference. ISPE Malaysia is looking at approaches and knowledge required to ensure compliance and patient safety within the context of our nation.”

The ISPE Malaysia Annual Conference provides participants and members with information on trends and technologies. In 2023, an entire session was devoted to regulatory trends and updates, with presentations by the NPRA, the Medical Device Authority, the Malaysian Green Technology and Climate Change Corporation, and the Malaysian Industrial Development Finance Berhad. The presentations updated participants on the latest developments in their respective agencies, as well as opportunities for assistance.

“The ISPE Malaysia event is unique in bringing all the agencies together in one conference,” Noordin said. “We had a lot of positive feedback and will continue with the regulatory track in our next conference. ESG [environmental, social, and governance] and sustainability are additional areas of great interest right now with publicly listed companies having to comply with lower carbon emissions and other targets by 2030. The ISPE Malaysia Affiliate has been asked to assist in developing technical documents and calculation tools to help pharmaceutical companies.”

Philippines

“Over the last few years, the pharmaceutical industry in the Philippines has shown significant market growth potential,” said Arnel Cabungcal, Operations Services and Technology, Unilab, Inc., and past president of the ISPE Philippines Affiliate. “This is highly reliant on the government’s interest in develop-ing the local drug manufacturing sector. Growth in Philippine healthcare is driven by a favorable demographic profile, rising chronic disease burden, and continued government commitment to universal healthcare. This is driving drug sales and is augmented by a government subsidy and increased private sector participation.”

Regulatory compliance in the country continues to improve with membership in ASEAN and an evolution toward PIC/S GMP standards. Despite these improvements, the domestic pharmaceutical industry relies almost solely on imports for the bulk of its supply for a growing population exceeding 117 million. Two-thirds of the pharmaceutical products supplied to the domestic market, and virtually all raw materials and APIs used to manufacture or formulate drugs are imported, with India being the largest supplier of pharmaceuticals to the country.7 The value of the country’s exports was only US $50 million in 2017, the last year for which data is available.7 As of 2016, the largest pharmaceutical company in the local market was Unilab, which had a market share of 25%.7

“All API supply and most raw materials are imported,” according to Vivien Santillan, Regional Director, Asia, Novatek International. “This high de-pendency on importation leads to drug shortages and the high cost of drugs. Multinational pharmaceutical companies have a presence, but only for dis-tribution or through engagement with CMOs [contract manufacturing organizations] for repacking or production. The Philippine industry consists pre-dominantly of generic manufacturers, typically for small molecule drugs. There are limited government incentives for local manufacturing but efforts from the Department of Trade and Industry through the Board of Investments have been established to spur adoption of Industry 4.0.”

Other than the challenge of building up domestic manufacturing, a state-of-the-industry report from the Philippine Competition Commission outlined several other challenges for the pharmaceutical industry in the country, notably that the regulatory environment in the country appears to be more stringent than others in the region.7 The challenges the report highlights include the following:

- A slow drug registration process that hampers getting products to market

- Lack of dialogue between industry and the Philippines Food and Drug Administration (PFDA)

- The presence of counterfeit drugs on the market

- Struggles to hire, and keep, qualified workers

- Large variations in drug prices depending on the seller or hospital

“Growth headwinds include challenging sustainability of the healthcare system, lack of healthcare facilities and workers, and low levels of intellectual property protection,” Cabungcal said. “Greater collaborative efforts by government and industry to suppress counterfeit drugs continue to provide an upside to locally developed generics.”

The ISPE Philippines Affiliate

“Since its creation in 2008, the ISPE Philippines Affiliate continues to drive the mission and vision of ISPE at the regional level, elevating members of our community as we create opportunities for collaboration and networking,” Cabungcal said. Representatives from regulatory authorities and government agencies make up 39% of the membership of the Philippines Affiliate, while 52% are students and recent graduates. “To help nurture the future work-force for the pharma industry, we collaborate with academic institutions, the industry, and professional organizations to foster capability of young professionals, conduct internship programs for pharmacists, and mentor students and emerging leaders.”

According to Cabungcal, the ISPE Philippines Affiliate, which won the Affiliate and Chapter Excellence Award in 2021, collaborates with the PFDA and industry associations to:

- Build technical competencies in GMP and other pharmaceutical technologies

- Explore anti-counterfeiting solutions and drug shortage prevention

- Develop pharmacovigilance and adverse event monitoring

“While there are different maturity levels with respect to technology and regulatory adoption within the APAC region, there is engagement with gov-ernment agencies to incentivize local manufacturing,” Santillan said. “The technical trainings provided through the ISPE Philippines Affiliate help update the industry on the trends, technologies, and the latest regulations.”

Vietnam

Vietnam has a long history of pharmaceutical manufacturing. For example, Sanofi, which operates a GMP facility in Ho Chi Minh City, has had a presence in Vietnam for more than 70 years.

“The pharmaceutical market in Vietnam still has growth potential with our population of more than 100 million,” said Bảo Nguyễn. “There has been a shift in production from other countries in the region, such as Indonesia and China, to Vietnam, and there is significant foreign investment in domestic companies.”

This includes SK Group (South Korea), which took control of Vietnamese drug manufacturer Imexpharm,8 ASKA Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Japan), which invested in Ha Tay Pharmaceutical,9 and Samil Pharmaceutical (South Korea), which opened a new facility in Ho Chi Minh City in 2022 to produce eye drops for global distribution.10

“Most companies focus on simple manufacturing techniques and low-value OSD [oral solid dosage] medicines, like paracetamol,” said Huy Nguyễn, Quality & Validation Engineer III, Terumo Blood and Cell Technologies. “There are more than 200 local pharmaceutical companies that can contribute to the medical security of Vietnam’s healthcare system.”

This is good news for the Vietnamese pharmaceutical industry, the value of which is pegged to reach US $8 billion in 2023.9 There are investments in technology for high-tech products, such as vaccines and pellets. Many of the manufacturers are CMOs for large pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer and AstraZeneca.

According to Bảo Nguyễn, the industry’s challenges include strong pricing competition from other countries in the region. Raw materials are mainly imported, with price and quality varying from batch to batch because Vietnamese companies often buy in small quantities. “As well, the layout of many facilities follows older concepts, requiring considerable investment to meet cross-contamination control requirements. There are limited human re-sources to follow GMP requirements, especially in small localities. Training is still limited, much of the hardware is old, and the processing is still manual and, as a result, has a lot of human errors.”

Huy Nguyễn agrees. “There are few people with the know-ledge of quality and validation, which is a prerequisite to get GMP certification. There’s a lack of appropriate levels of investment in quality management systems, manufacturing equipment, and facility design. This results in low quality man-agement and, unfortunately, compliance issues. The unique challenge is the willingness of leadership to invest in quality.”

A case in point. The Drug Administration of Vietnam recently sanctioned a pharmaceutical manufacturer of methotrexate for quality violations.11

“I’m hopeful these challenges can be met by building a quality system to meet new requirements, learning from training courses from organizations around the world, and taking advantage of human resources from global companies in Vietnam, like Sanofi,” said Bảo Nguyễn. “We can also invest in new hardware systems and research products with high economic value.”

Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand are blessed with a highly skilled labor market, along with strong research and development (R&D) in science and technology at universities that drives innovation, including clinical-scale ATMP production and chimeric antigen receptor T cell innovation. Both countries are at-tractive spots to run clinical trials because they are English-speaking and, in Australia’s case, the government offers a significant tax break on clinical pro-jects. As a result, contract research organizations are prevalent. Combined with their proximity to the abundance of relatively cheap labor in Asia, this means the traditional biopharmaceutical industry is quite small in both countries.

“It’s true, we can’t compete in terms of low-cost labor,” Wakeham said. “Ten years ago, I would have said pharmaceutical manufacturing was in de-cline in Australia when we lost some of the global multinationals.”

“Over recent years, there was an exodus of larger manufacturing companies from New Zealand and Australia,” said Parlane. Some have recently shut down sites in Australia, including Pfizer and GSK, which closed its Boronia site at the end of 2022 after 50 years of operation. “The extended amount of time without larger firms manufacturing in New Zealand means there is a lack of technical expertise and recent experience, making it difficult to stand up even modest-sized projects in that country.” Australia has critical mass in terms of its industry and local regulators.

There are, however, signs of a resurgence in the industry. Australia continues to have a strong biotech and R&D sector, with many research facilities. Moderna announced in 2021 that it will produce millions of doses of mRNA vaccines annually, and BioNTech has plans to open a research center and manufacturing site. The New South Wales government is building a large viral vector manufacturing facility, which will be put out to tender for a private company to operate.

New Zealand has established vaccine manufacturing capabilities since COVID-19, albeit on a small scale. And, in both Australia and New Zealand, the rise of the medicinal cannabis industry has seen expansion of GMP manufacturing. In Australia, for example, the number of new patient receiving a pre-scription for medical cannabis in the first six months of 2023 more than doubled over a similar period in 2022.12 Although sales were estimated at only US $67.4 million in 2022, the market is projected to continue to grow rapidly over the next decade.13 In addition, Tasmania is the largest producer of legal opioids, including morphine, thebaine, and codeine.14

“And New Zealand continues to be a hub for veterinary medicine manufacturing,” said Parlane. “We have also seen steady growth in GMP manufacturing of low-risk listed medicines primarily for the Australian market.”

Quality and compliance are also strengths. The TGA is an active and respected partner in many regulatory forums, including PIC/S and the International Medical Device Regulators Forum. This means TGA approaches are usually well-aligned with GMPs from both the US and Europe.

“TGA hosts inspector trainings that are open to other regulators in the region, helping to raise the overall standard of inspection throughout the re-gion,” Wakeham said. “I’ve presented at their inspector training sessions and found regulatory acquaintances attending from Thai FDA, Medsafe, and others.”

Japan

Japan is the third-largest pharmaceutical market in the world, though it is expected to shrink while the rest of the global market grows.15 Despite the size of its pharmaceutical market, Japan’s production of new drugs declined in recent years with only one of the top 20 drugs, by revenue sales in 2020, having been developed in the country.16

Despite this, the industry does exhibit strengths. There has been a renewed focus to improve the country’s drug discovery system and exports have increased dramatically since 2020. 15 Japan’s biopharmaceutical market is projected to grow despite the downturn of Japan’s total pharmaceutical market, and the industry’s use of artificial intelligence in drug development is significant.15

“Japan has robust intellectual property protection laws, encouraging innovation and providing a supportive environment for pharmaceutical compa-nies to invest in R&D without significant concerns about intellectual property theft,” said Hirokazu Kisaka, Vice President, Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd, and ISPE Japan Affiliate chair. “Japanese pharmaceutical companies have a strong track record in R&D. We invest significantly in innovative and cutting-edge re-search, leading to the discovery and development of novel drugs and therapies.”

Kisaka noted that, like many jurisdictions around the world, the Japanese pharmaceutical industry may face shortages of skilled professionals. “Train-ing, attracting, and retaining talent is essential for the continued success of the pharmaceutical sector.”

The ISPE Japan Affiliate tries to help meet this challenge. “Our purpose is to contribute to revitalizing the industry and increasing competitiveness in the world,” Kisaka said. “We can provide the opportunity for members of the pharmaceutical industry to gather to exchange the latest information on business environment, technology, regulatory, and overseas affairs.”

Conclusion

The biopharmaceutical industry throughout APAC is developing rapidly, propelled by strong government support, regulatory reforms and international cooperation, an influx of venture capital, and a desire to adopt technological innovations. Its ability to evolve and adapt to meet challenges continues to mean it can deliver legacy drug products and develop innovative therapies to supply both domestic and global markets.