An Evaluation of Postapproval CMC Change Timelines

As the demand for accelerated access to medicines expands globally, the pharmaceutical industry is increasingly submitting regulatory applications in multiple countries simultaneously. As a result, Boards of Health (BoHs) are challenged with approving these applications in an accelerated timeframe and accommodating the submission of postapproval chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) changes that pharmaceutical manufacturers submit after implementing improvements or optimizations.

Among global BoHs, variability in regulatory requirements and approval times for postapproval CMC changes has created an inordinately long delay between the first and last approval for a single CMC change for a pharmaceutical product. These long global approval timelines complicate supply chain management by delaying innovations that improve quality assurance and by increasing the potential for supply interruptions and shortages that impact patient access to products.

In this article, we describe the assessment of lag time for global regulatory approvals of postapproval CMC changes for multiple products over a three-year period. This approach incorporates all factors that influence the time for BoH approval as experienced in real-world situations and is relatively straightforward to calculate. It also allows for comparisons between companies and across different periods of time.

“In scope” were changes that required the most detailed BoH assessment in an impacted country (either by a notification or prior approval). For each country, the time required to achieve 90% probability of approval for a change represents the time between the first approval and each subsequent country BoH’s approval for that change. We believe this represents the most relevant measure to assess the duration and impact on implementation and reflects the largest degree of complexity faced by industry to support postapproval CMC changes.

The results show that the time to achieve a 90% probability of approval for that change is ≥ 24 months in 63% of countries studied and ≥ 36 months in 15% of countries studied. In addition to delaying optimization of manufacturing and controls, these types of long delays for approvals discourage continuous process improvements for approved products.

We hope the results from this assessment stimulate adoption of the World Health Organization (WHO) Good Regulatory Practice (GRP) as well as implementation of International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidance that would improve the quality assurance of medicines for patients, decrease wait times with regulatory authorities, and reduce complexity and costs for industry.

Variability of BOH Approvals

The time it takes to achieve global regulatory BoH approvals of postapproval CMC changes varies considerably around the world. The assessment of how long it takes to achieve global approval for postapproval CMC changes provides compelling data to improve regulatory processes, as the expedited implementation of optimizations for manufacturing and control of products increases quality assurance for patients globally.

The WHO is driving implementation by BoHs of GRP, which will improve regulatory processes.1 The risk of a change to patients is inherent to the change itself, not in which country it is being reviewed. On this basis, it seems appropriate that there should be greater global consistency in the regulatory processes, data requirements, and BoH assessment durations required to establish the suitability of a change.

Previous publications on this subject provide general information on BoH assessment timelines (e.g., > 24 months).2, 3 The assessment described herein includes recent “real world” data to describe the increasing probability of approval over time after the first global approval for a particular change. Taking Kuwait as an example (using data in Table 2), after the first approval for a change (anywhere in the world), there is a 50% chance of approval of that change in Kuwait within 24 months and a 90% chance of approval within 43 months.

Postapproval CMC changes have several drivers. For example, a site of drug substance or drug product manufacture may be moved and/or added to effectively manage product inventory and ensure supply chain reliability; a manufacturing process may be modified to introduce innovation or efficiency; or it may be necessary to modify the drug substance or drug product specifications during the life cycle of a product to accommodate changes in regulatory standards or expectations.

For each BoH, the time for approval of a change is influenced by the local regulatory framework, i.e., statutory requirements, regulatory guidance and prioritizations, data standards and requirements, BoH assessment criteria, and resource capacity. Considering regulatory frameworks, many BoHs, such as the United States (US), European Union (EU), United Kingdom (UK), Japan, and Canada, have filing categories (i.e., do and tell; tell, wait, and do; and prior approval) that are aligned with the potential risk to critical quality attributes associated with safety, efficacy, and quality of the product.

Pfizer regulatory teams local to the impacted countries have reported that in some countries, the marketing application authorization (MAA) of a drug is granted based on a specific supply chain and that the introduction of an alternate source of supply after approval requires the submission of a new MAA (e.g., Bolivia, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Philippines, and Vietnam). In these countries, a secondary packaging site change or an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing site addition triggers a new submission equivalent to that required for approval of a generic drug or a line extension, whereas these site changes may be filed as a notification in the US and EU.

Additionally, Pfizer regulatory teams local to the impacted countries have reported that some rest of the world (ROW) countries require prior approval from a country that is also dependent upon prior approval in a third country. For example, Russia can require a sample at submission (based on approval from EU or other country). Subsequently, Armenia requires prior approval from Russia before the submission can be made in Armenia.

This sequence of submissions and approvals can significantly extend the time to final regulatory approval and is not in proportion to the risk of the change to patients. The WHO GRP contains the concept of mutual reliance and recognition, meaning that one or more countries can accept the assessment outcome from a reference country. Such reliance would reduce the time to approval in some countries and avoid the need for repeat assessment of a change that may have been reviewed, approved, and already be in distribution to patients in the first approving countries.

Long global approval timelines complicate supply chain management by delaying innovations that improve quality assurance and by increasing the potential for supply interruptions and shortages that impact patient access to products.

The BoHs listed previously have well-defined data requirements; however, in the ROW, many countries have additional data requirements for the submission of a change. Due to the differences in the data (e.g., duration of stability data at time of submission) required by a BoH to support a postapproval CMC change, submission dates can vary by months or years between the first and last countries, due, in part, to the need to wait for additional and extraneous data. The ICH develops guidance for harmonization of data requirements for a postapproval CMC change.4 However, these guidelines are not always interpreted or implemented consistently by country BoHs5

Increasing the capacity of a BoH, through implementation of WHO GRP and Good Reliance Practice, is a strategic focus of the WHO and the International Pharmaceuticals Regulators Forum.1, 6 This implementation is designed to benefit all activities undertaken by the BoH, including the review of postapproval CMC changes, thereby optimizing BoH assessment times.

Improved alignment of regulatory processes will undoubtedly increase implementation of manufacturing optimizations, reduce the potential for drug shortages, lower the costs associated with managing inventory complexity, and encourage continuous improvement to increase quality assurance, particularly for approved older products.2, 3

Methods

The total time to approval of a global postapproval CMC change was measured, using data from Pfizer’s GMP systems, as the time between approval in the first country to approval in each of the other countries impacted by that change. Table 1 shows a hypothetical example of how the assessment was performed. For each change, the time from first approval to approval in country A was recorded. Similarly, the time from first approval to approval in country B was recorded, and so on for all countries (represented by N) affected by the change. Then the durations were compiled for analysis and presented in the table.

| Change Number |

First Approval for the Change Anywhere in the World |

Approval in Country A |

Duration from the First Approval of a Change to Approval for that Change in Country A (months) |

Approval in Country B |

Duration from the First Approval of a Change to Approval for that Change in Country B (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Feb 2017 | 1 Feb 2018 | 12 | 1 Feb 2020 | 36 |

| 2 | 1 Jun 2019 | 28 Nov 2019 | 6 | 23 Nov 2019 | 18 |

| 3 | 1 Sep 2019 | 30 Nov 2019 | 3 | 28 May 2020 | 9 |

| N | 1 Mar 2020 | 29 Jun 2020 | 4 | 24 Dec 2020 | 10 |

| Time after the first approval for a change, giving a 50% chance of approval in country A |

5 | Time giving a 50% chance of approval in country B |

14 | ||

| Time giving a 90% of chance of approval in country A | 10 | Time giving a 90% of chance of approval in country B |

31 | ||

For each country, only those changes with the highest assessment impact were included (e.g., Type II in the EU or a Prior Approval Supplement [PAS] in the US), as these would represent the greatest level of complexity for manufacturing and supply operations. In many countries, a prior approval category was required, but in other countries a notification of the same change was acceptable. BoH approval was based on either evidence of submission for a notification to a BoH or a BoH approval letter.

Scope

The scope of the assessment was for country approvals received in the calendar years 2018–2020. The first global approval for a change covered by one of these country approvals could have been received before 2018 and was needed for the calculations. On this basis, country approvals covering 2016–2020 were included in the analysis.

The countries impacted by a change should come from more than one geographical region to ensure a range of countries were involved. A country was in scope if it had 10 or more changes approved during 2018–2020, which was the minimum number for which a percentage analysis is considered valid.

Data were collected for over 5,900 postapproval CMC changes that translated to 20,000 country submissions with approvals in 2016–2020. Of these, over 790 changes in over 3,575 country submissions covering 97 countries were in scope. Changes were considered out of scope if they did not use the highest assessment impact regulatory process (e.g., Type IA/IB/CBE30 or notification in a country with a prior approval category) or if the change was only applicable in a single region.

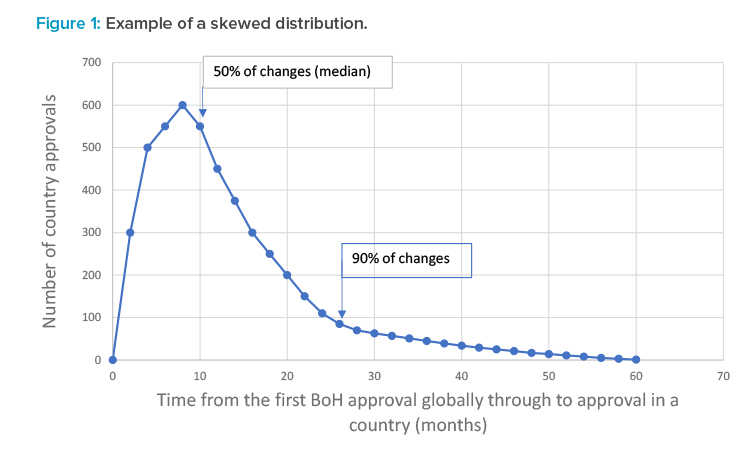

Because the duration to submit, review, and approve in each country was variable, depending on the type as well as on the BoH prioritization of change, two representative durations were determined: the duration after the first global approval for a postapproval CMC change to achieve a 50% probability of approval and the duration after the first global approval for a postapproval CMC change to achieve a 90% probability of approval. For each country, the durations measured showed a skewed distribution, meaning that averages and standard deviations were not applicable. Figure 1 shows a hypothetical example of a skewed distribution and the indicative position of the duration giving a 50% chance of approval and a 90% chance of approval.

The duration required to achieve a 90% probability of approval of a postapproval CMC change in a country (after the first global approval for that change) reflects the increased complexity required to manage the supply chain for these products and the concomitant impact to supply chain reliability. The duration to achieve a 90% probability of approval of a change was chosen because capacity and inventory management can effectively meet extended durations for the remaining 10% of approvals through stock builds. The duration to achieve a 90% probability of approval is simple to calculate and can be comparable across global companies and through time.

Results

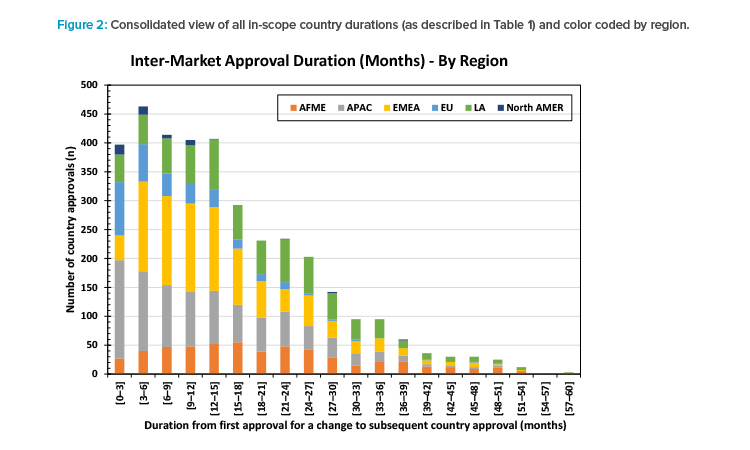

Figure 2 shows all the durations from first approval for a change to each country approval for that change (as described in Table 1) from the 3,575 in-scope country submissions. The skewed distribution is clear. The tail of approvals taking longer than 36 months can be seen. The long tail is the source of the greatest complexity for manufacturing operations.

For 47 of the 97 countries (48%), the time needed to achieve a 90% probability of approval of a change was ≥ 24 months but < 36 months after the first BoH approval for that change. There was a 50% probability of approval of a change in 94 of 97 countries within 24 months and all within 36 months of the first BoH approval for that change.

| Country | Region | Duration from First BoH Approval to Country Approval (months) |

Data Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Botswana | AFME | 51 | 14 |

| Jamaica | LA | 48 | 29 |

| South Africa | AFME | 45 | 24 |

| Kuwait | AFME | 43 | 49 |

| Oman | AFME | 41 | 26 |

| Jordan | AFME | 40 | 31 |

| United Arab Emirates | AFME | 40 | 45 |

| Iraq | AFME | 39 | 39 |

| Morocco | AFME | 38 | 41 |

| Dominican Republic | LA | 37 | 72 |

| Curacao | LA | 37 | 43 |

| Namibia | AFME | 36 | 26 |

| Panama | LA | 36 | 61 |

| Kosovo | EMEA | 36 | 63 |

| Palestine | EMEA | 36 | 41 |

Table 2 shows the time needed to achieve a 90% probability of approval of a change (after the first approval for that change) for each of the 15 countries (15%) where the duration was ≥ 36 months after the first BoH approval for that same change. The durations were measured from first BoH approval for a change to that individual country’s BoH approval for that change.

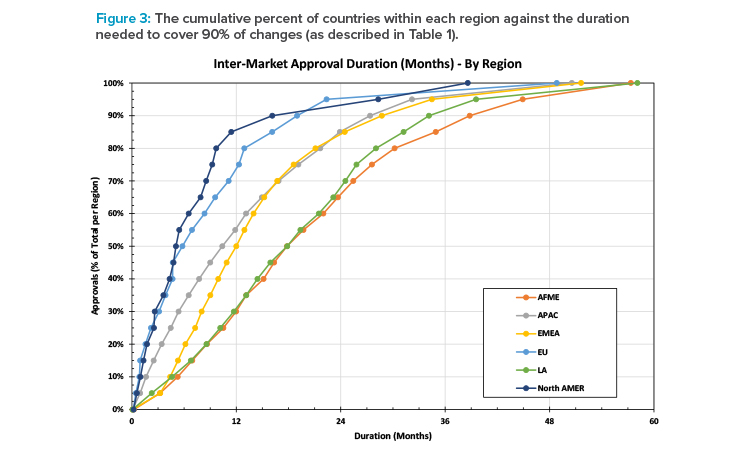

Figure 3 shows the cumulative percent of approvals by region against the number of months needed to achieve BoH approval after the first BoH approval for a change. It shows the spread of durations by region. For example, in North America, it takes approximately 16 months to achieve approval of 90% of submissions (after the first approval for that change), whereas in AFME it takes approximately 39 months to achieve the same milestone.

Discussion

It is well known that it can take several years to achieve BoH approval for a single postapproval CMC change.2, 3 The results of this current assessment measure the duration for BoH approval on a per-country basis for approvals received over a three-year period. Included in the duration to approval for each country affected by the same change are the relative impact of the change requirements in addition to the first country, constraints on submission times, and the impact of queries on approval time and the BoH assessment duration.

The time from first country BoH approval for a postapproval CMC change through to achieving approvals in the other countries impacted by the same change is the time through which manufacturing and supply chain teams need to manage different product inventories. The longest durations are those associated with changes going through the most rigorous assessment category available within the country. Consequently, the focus of the analysis was on this subset.

The results show that there is a 50% chance of approval of a change in all but three of the 97 countries in less than 24 months after the first approval. These 50% generally do not represent the main source of supply management challenges. Hence, it was necessary to establish a measure that captured the changes that take longer to approve and are more likely to become supply chain management and reliability concerns. The duration to achieve a 90% probability of approval of a change was chosen as the measure identifying supply chain management and reliability concerns.

In the dynamic global environment, the approval times for postapproval changes can be expected to change over time and may well differ between pharmaceutical companies based on different practices and approaches. Consequently, comparing results across companies and through time will establish an increasingly robust perspective of trends in global approval durations.

The results show that it can take over three years from approval in the first country to achieve a 90% probability of a country approval of that postapproval CMC change. Frequently during a three-year window, multiple CMC changes for a specific product will be submitted for global approval. Ostensibly, this significantly increases the complexity of managing multiple inventories and parallel supply chains for the same product simultaneously. This level of complexity increases the probability of affecting the reliability of supplies for every market.

| Factors Contributing to Long Durations | Proposals to Mitigate Prolonged Approval Times |

|---|---|

| The stability data required at submission can vary from zero to six months in US and EU to > 12 months in some countries. |

Align requirements with global regulatory standards, e.g., ICH or a reference country |

| Changes cannot be submitted during an ongoing agency review of a change or a renewal (e.g., Brazil, South Africa), requiring sequencing and prioritization of submissions. | Create capacity by adopting GRP. Match requirements to the implications for patients, enabling parallel submissions. |

| The requirement for BoH approval regardless of the level of risk associated with a submission (i.e., no option for notifications). For example, a change covered by a notification in US or EU requires a new application in some countries. |

Adopt a tiered approach such as that used in the EU or US. |

| Duration of BoH assessment of changes. | Reduce assessment durations by increasing capacity and adopting GRP, which includes mutual reliance and recognition, aimed at reducing workload for regulators and the time to approval. |

| Multiple iterations of BoH queries, many of which are not scientifically focused. | Improve risk-based approaches to regulatory reviews of postapproval changes, i.e., impact of change on product-critical quality attributes associated with quality, safety, and efficacy. In addition, consideration of mutual reliance and recognition, particularly when the change has already been effectively implemented in many countries globally. |

| BoH statutory framework, i.e., some BoH require a separate and specific licence for each manufacturing site. Consequently, any change in the manufacturing site requires a new submission rather than a postapproval change. | Legislation should be framed around the product rather than the site of manufacture. |

Table 3 summarizes the factors that contribute to prolonged approval times based on experiences reported by Pfizer regulatory teams local to the impacted countries and proposes actions BoHs can implement to mitigate those prolonged approval times. The proposals are consistent with WHO GRP.

Existing regulatory frameworks

In the 1950s and 1960s, the WHO published documents outlining how countries should set up a regulatory framework to control pharmaceuticals and ensure the safety of their subjects. In parallel, the certificate of a pharmaceutical product (CPP) process was developed, enabling certain regulatory authorities to confirm approval and thus serve as reference for the basis of approval for products scheduled for import into other countries. Because regulatory legislation in different countries has developed independently, many different and sovereign approaches have evolved.7

Reducing the prolonged duration for global approval of postapproval CMC changes will require improved alignment of data requirements; adoption of appropriate risk-based assessments that are proportional to the risk of a change to the critical quality attributes associated with product quality, safety, and efficacy; and alternatives to address BoH capacity constraints, i.e., mutual reliance and recognition, including cooperation between countries in evaluation.

These needs are all consistent with WHO GRP for regulatory oversight of medical products and “good reliance practices in regulatory decision-making for medical products” as well as the work of ICH covered in the mission statement and such publications as ICH Q12 “Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management.”1, 4, 8 ICH Q12 provides a framework demonstrating how increased product and process knowledge can contribute to a more precise and accurate understanding of which postapproval changes require regulatory submission (Established Conditions). Postapproval change management protocols can be used to gain agreement among regulators about which requirements can be used to demonstrate acceptability of a change. In both cases, the level of reporting categories for changes can be agreed upon in advance.

Categories of change

The US and EU (among others) have developed categories of change depending on the change type and associated risk, with a clear set of requirements and timelines9 Some of these categories can be handled through notifications or annual reports rather than through prior approval applications. The EU has adopted procedures where the evaluation by one or more countries is recognized by other countries in the group (i.e., the Centralized, Mutual Recognition (MRP), and Decentralized (DCP) procedures).

In recent years, several countries have adopted the EU approach in terms of categories and filing types (e.g., South Africa, some Gulf countries) and introduced forms of cooperation and reliance to reduce the assessment burden across the group (e.g., the Gulf Cooperation Council, Association of Southeast Asian Nations). Unfortunately, some countries also retained their local requirements, and most did not implement the associated review timelines. Few ROW countries have published commitments to assessment durations. In some instances, the capacity of the regulator to process the changes submitted appears to be incompatible with reasonable assessment durations. Adoption of GRP would help balance resource and capacity in these countries.

Some countries have attempted to mitigate the long duration to BoH approval by introducing a process by which a special import permit can be requested when the time to BoH approval is impacting continuity of supply. However, organizing these permits demands additional time and capacity that should not be needed if the regulatory framework and associated infrastructure in those countries was consistent with GRP.

Approaches should be adopted that are consistent with GRP and provide alignment, clarity, and consistency of requirements, submission types, and appropriate regulatory timelines in accordance with risk-based assessments of postapproval CMC changes. Global adoption of GRP encourages manufacturing innovation by removing barriers to continuous improvement and ensures reliable and sustainable supply of medicines to patients globally.

Conclusion

This exercise provided a comparative assessment of global approval times for postapproval CMC changes between 2018 and 2020. The results highlight the manufacturing and supply complexity associated with prolonged global approval times for each postapproval CMC change. In addition, the duration to achieve a 90% probability of approval of a change in a country represents the cohort of changes likely to be associated with supply issues and increased manufacturing complexity.

The finding that 15% of the 97 countries evaluated can take ≥ 36 months from first approval for a particular postapproval CMC change through to having a 90% chance of approval for that change in all other target countries represents a challenge for industry and the patients it serves. That the data obtained indicates that 63% of countries need ≥ 24 months to have a 90% chance of approval should also be considered to support advocacy in this area.

Implementing global best practices in medicines regulation to reduce the time from first to last approval for a global postapproval CMC change would minimize the cost of managing CMC changes for both regulators and industry. Such implementation would also reduce waste, create a more robust supply chain, and increase the alignment of products dispensed to patients globally.