Hands-on Innovation Management with the ISPE Hackathon

Innovation is an integral part of corporate strategy. Initiatives to facilitate innovation are continually developed and pursued. The 2022 ISPE Pharma 4.0™ Emerging Leader (EL) Hackathon was designed based on innovator needs and provided a hands-on blueprint manufacturing exercise. Over a period of two days and facilitated by 40 subject matter experts, coaches, and jury members, 50 participants explored Pharma 4.0™ solutions at a cell and gene therapy (C>) manufacturing site.

Introduction to the Pharma 4.0™ Concept

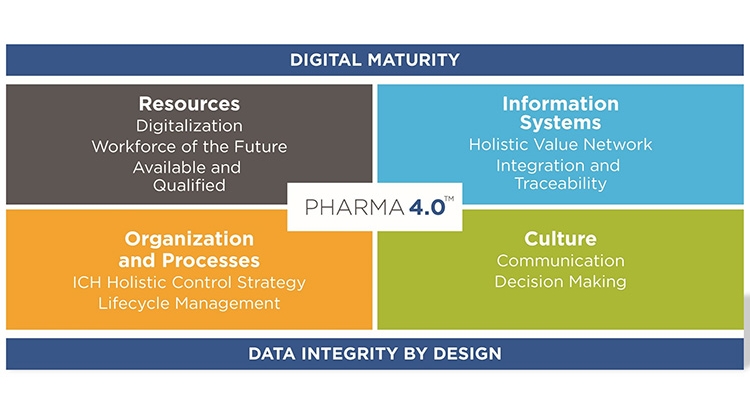

Pharma 4.0™ is the adaptation of the concept of Industry 4.0 to the pharmaceutical industry and an example for a highly complex emerging technology. The concept was established and is continually driven by the ISPE Pharma 4.0™ Community of Practice (CoP). Among other resources, the CoP developed an operating model that reflects the complexity of the field (see Figure 1).

The 12 theses for Pharma 4.0™ provide a framework for activities:

- Pharma 4.0™ extends and describes the Industry 4.0 operating model to medicinal products.

- In contrast to common Industry 4.0 approaches, Pharma 4.0™ embeds health regulation best practices.

- Pharma 4.0™ breaks silos in organizations by building bridges between industry, regulators and healthcare, and all other stakeholders.

- For next-generation medicinal products, Pharma 4.0™ is the enabler and business case.

- For the established products, Pharma 4.0™ offers new business cases.

- Investment calculations for Pharma 4.0™ require innovative approaches for business case calculations.

- Prerequisite for Pharma 4.0™ is an established pharmaceutical quality system (PQS) with controlled processes and products.

- Pharma 4.0™ is not an IT project.

- The Pharma 4.0™ Operating Model incorporates next to IT, organizational, cultural, process, and resource aspects.

- The Pharma 4.0™ Maturity Model allows aligning the organization’s operating model with innovative and established industries, suppliers, and contractors to an appropriate desired state.

- Pharma 4.0™ is not a must, but a competitive advantage. Missing Pharma 4.0™ might be a business risk.

- When moving from blockbusters to niche products and personalized medicines, Pharma 4.0™ offers new ways to look at business cases.

Pharma 4.0™ Hackathon Insights

Innovation is an essential element of today’s corporate strategies. Corporations pursue innovation in multiple ways.1, 2, 3, 4 Corporate venturing refers to activities beyond conventional internal research and development, designed to accelerate, create, capture, and deliver innovation.5,6 This is performed by managing and executing an individual set of corporate innovation initiatives (CIIs).

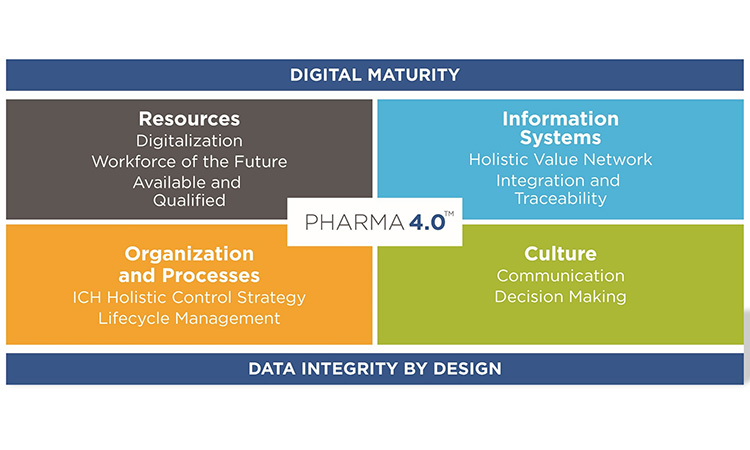

Execution of the later-described CIIs enabled the holistic exploration of Pharma 4.0™. During the Hackathon, five workstreams were conceptualized with subject matter experts from the industry (see Figure 2). The hands-on mentality was reflected in the practical use cases of each workstream. Workstream content and outcomes are described next.

Workstream 1: System and Data Architecture

A process was set up where coffee was mixed with milk and the temperature was controlled. All hardware components were integrated via Module Type Package (MTP) and connected to an overarching process orchestration layer (POL). Separately, three colored liquids were mixed, and the results were observed via spectrometry. By using advanced process control (APC), a model could be developed and verified to achieve a target state.

Insight: The workstream provided proof of concept of the effective application of plug and produce and APC to increase quality.

Workstream 2: Operations and Workflows

The participants explored a validated online software as a service (SaaS) environment. Based on a paper-based batch record, they built an app that guides an operator through part of a manufacturing process.

Insight: A proof of concept for an electronic batch record (eBR)—an integrated digital operating guide with full documentation—was set up and demonstrated within a verified SaaS environment.

Workstream 3: Shopfloor Integration

A risk-based approach guided the participants in exploration of process analytical technologies (PAT). Raman and dielectric spectroscopy were selected, integrated, and applied in a demo setup.

Insight: PAT enables the in-line measurement of critical process parameters (CPPs) and serves as a key enabler for real-time process control.

Workstream 4: Quality and Validation

The participants developed a holistic control and validation strategy in close exchange with other workstreams.

Insight: Data- and risk-based validation drives quality along the entire value chain.

Workstream 5: Simulation and Data Analytics

The group explored different provided data sets and software solutions. They set up and applied digital twins, in silico simulation for APC, and economic modeling.

Insight: A holistic digital twin architecture connects different stakeholders and serves as a base for leveraging process information in control and optimization.

Winning Workstream

After two days of hands-on exploration and presentations, the jury selected workstream 5 as the winning team. As of writing, further exploration of the prototyped potentials are planned to be explored as a workstream within the Pharma 4.0™ CoP Plug and Produce working group.

Corporate Venturing

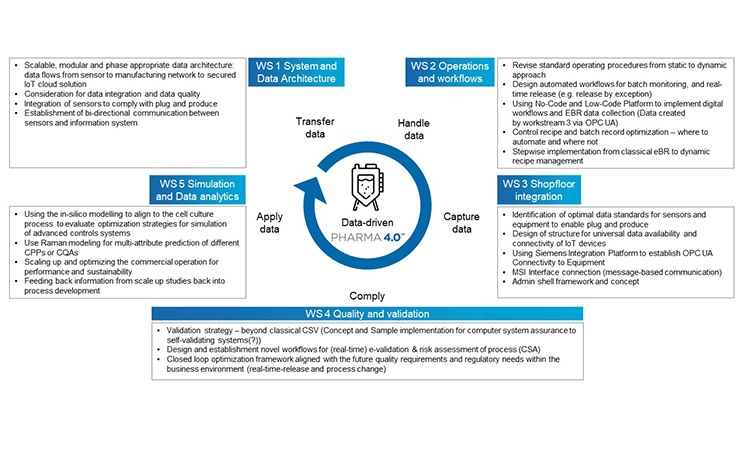

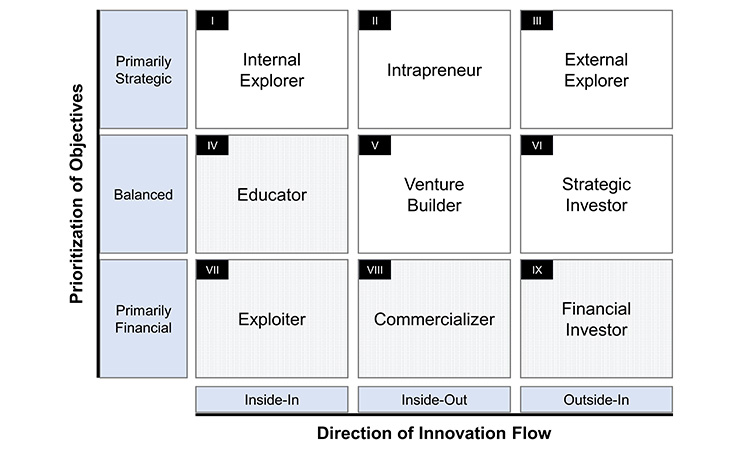

In recent years, corporate venturing has received increased attention, resulting in a growing number of presented CIIs.7 Some CIIs, such as accelerators and incubators, emerged dominant but remain rather vague.8 Overall comparability between CIIs is described as low, which limits the effectiveness of corporate venturing research and keeps practitioners lost.9, 10 Recently, frameworks to cluster CIIs and put them in context to each other emerged. The framework by Gutmann et al. applies the dimensions of innovation flow and the prioritization of the CII’s objectives, resulting in a 3×3 matrix (see Figure 3).11, 12, 13 In the figure, highlighted modes of corporate venturing (IV, VII, VIII, and IX) refer to exploitation, and the others (I, II, III, V, and VI) refer to the exploration of technology.

Corporations usually prefer to have a balanced portfolio of CIIs with regard to the individual context of the organization. This structured approach toward CIIs is referred to as corporate venturing management.

Innovation Management Characteristics in High-Tech Industries

In multiple high-tech industries, such as the chemical and biopharmaceutical industry, innovation is a key element of business value.14 Corporate innovation management comes with several characteristics, and we discuss a selection of these next. When designing a novel initiative, these characteristics need to be considered to enable efficient innovation.

Technological Complexity

Emerging technologies such as digitalization come with enormous complexity. Many internal and external stakeholders are involved. Novel technologies continuously emerge from inside and outside the organization.14

Ambidexterity

Ambidexterity refers to the capability to exploit incremental innovation while exploring radical innovation for lasting success. It is seen as a key challenge for corporate innovation management.14

Ivory Tower Syndrome

Ivory tower syndrome refers to the gap between the scope and aims of central management functions and the between functions on the operations level (e.g., at manufacturing sites) due to different routines and target systems.14

Outside View

Outside view is essential to innovation.14 In conventional research and development (R&D), ideas emerge from within the corporation and little focus is put on external assessment of their quality. In the early 2000s, the term “open innovation” was shaped and became an established part of today’s innovation management. 14

Efficient Innovation Management

Budgets are clearly defined, structured, and reported. Budgets without clear purpose are avoided. As a result, there is little flexibility to spontaneously support promising but uncertain innovation projects.14 In contrast, dedicated innovation units require high innovation output to justify themselves against higher management.

Fuzziness at the Front End of Innovation

The fuzziness refers to the uncertainty in innovation. Within the creative innovation process, it is not clear where and when ideas emerge and how innovation can best be ensured.15

Shift in Required Competences

The implementation of novel technologies as a result of the innovation process often requires additional competences in the workforce. This might be realized via training or hiring people with specialized skillsets.

Open Platform and Reach

Corporations are limited to their own reach. Including external innovators comes with discussion regarding intellectual property and compliance. This increases the complexity and hurdles to execute or even start an initiative.

Project Methods and Setup

In this article, we used the framework by Guertler et al. 16 to guide us through the development of the CII. The different phases are described next.

Analysis and Framing

The project was initiated, and the general scope and framing were derived. Objectives and results were defined. The core planning team regularly engaged and planned over a period of six months.

Project Planning

Project planning began with multiple interviews to gain a detailed understanding of prior projects. Afterward, the core team was defined and a digital infrastructure for collaboration was set up. The planning was differentiated in general organization, participant acquisition, development of content (five workstreams), and onsite organization. The five workstreams were developed by individual industry expert teams within a harmonized framework provided by the core team.

Execution on Action

The execution phase lasted two days and brought together the organization team, jury, host, industry expert teams, and participants.

Reflection and Learning

Discussion during the event and dedicated feedback sessions afterward allowed for insights from the different stakeholders.

Communication and Pivoting

Communication was split between methodological results and content results. The methodological results were documented and communicated to support more of such events. The content results were handed over to the relevant continuous expert group within the umbrella association.

Open Innovation Initiative for Exploration of Complex Emerging Technologies

When a new CII is developed, the objectives and innovation flow need to be considered. The novel CII presented in the rest of this article is located in the sectors of External Explorer and Strategic Investor. In addition, the presented characteristics of corporate innovation management need to be addressed. Subsequently, characteristics of the novel CII can be derived and are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristics of Corporate Innovation Management | Features of Proposed CII |

|---|---|

|

Complexity

|

|

|

Ambidexterity

|

|

|

Ivory tower syndrome

|

|

|

Outside view

|

|

|

Efficient innovation management and budget allocation

|

|

|

Fuzziness at the front end of innovation

|

|

|

Shift in required competences

|

|

|

Open platform and reach

|

|

The features in Table 1 guide the development of a novel CII. In essence, the proposed CII brings together multiple stakeholders from across the ecosystem. The chairing organization is a nonprofit industry association with the aim of knowledge exchange and knowledge transfer. The CII includes six dedicated roles (see Table 2) and a specific operating schedule (see Table 3).

| Role | Description | Motivation |

|---|---|---|

| Chairing organization | A nonprofit industry association, bringing different stakeholders together. Ensures exchange, marketing, and contracts as a neutral third party. |

|

| Management team | The core organization team is connected via the chairing organization. It volunteers as part of its engagement within the chairing nonprofit organization. |

|

| Jury | The jury provides management insights and consists of senior members of the chairing organization and the hosting company. |

|

| Participants | Participants are senior students or young professionals. Participants apply including a workstream preference and are selected based on motivation and qualification. |

|

| Hosting company | A manufacturing organization with facilities and to host the event. Connection to the management team and commitment to knowledge transfer to young professionals. |

|

| Workstream coaches | Each workstream focuses on a subtopic within the overall problem statement and is managed by different coaches coming from suppliers, i.e. from sensorics, data analytics, software. |

|

| Phase | Step | Content and key reference |

|---|---|---|

| Initiate | 1 | Identify roles, setup infrastructure, and define overall problem statement. |

| Develop | 2 | Develop content per workstream, including continuous alignment regarding feasibility with the hosting organization (IT infrastructure, availability of equipment etc.). |

| 3 | Acquire, screen, and select participants. | |

| Execute | 4 | Common introduction and motivation via the overall problem statement. |

| 5 | Exploration and conceptualization per workstream. Breaks and evening events for exchange between the workstreams and networking. Overall duration depending on complexity of problem statement. | |

| 6 | Pitch presentations from participants per workstream to communicate gained insights by participants. Jury evaluation and closing. | |

| Sustain | 7 | Results are documented and communicated. Further potential for proof of concepts, feasibility studies and minimal viable products are followed up on. Support the organization of other such events. |

Conclusion

Increasing innovation performance is one answer to face increasing volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) conditions. Central innovation management functions aim to increase the scope and reach of innovation activities by managing and executing CIIs. Exploration of emerging technologies enables early integration and can therefore drive competitive advantage and business value.

This article shows how strategic corporate venturing can be applied to address specific innovation needs and the results of the 2022 ISPE Pharma 4.0™ Emerging Leader Hackathon act as an example for the success of the proposed CII. The event brought experts and young professionals together and allowed for a holistic exploration of Pharma 4.0™. The gained insights were shared at a conference and are being further developed.