Wet Granulation Knowledge Brief

What is Granulation:

Granulation is the process of joining multiple particles or grains together, typically using a binding agent although mechanical force has been used to bond the particle together as well. This brief will provide the reader with a basic understanding of the options available for wet granulation as well as the processing implications. Before moving on, the terminology of granulation versus agglomeration should be addressed. In a purely scientific sense these are synonymous but in the pharmaceutical industry, agglomeration is often used to describe over-granulation or forming granules too large or out of specification.

Why Granulate Pharmaceuticals:

The most common reason to granulate pharmaceuticals is to prepare the material to obtain the physical properties needed to facilitate compression into a tablet. The binding agent works to hold the individual granules together so the tablet, after ejection from a tablet press die, maintains it integrity. Other reasons are generally centered on improving the processing or handling of the powdered material. Un-granulated material is often very dusty, creating housekeeping problems, operator exposure issues and product loss. Granulated materials flow better, improving processing speeds and yields. Lastly, physical characteristics such as bulk density, porosity, hardness, particle size distribution, morphology and robustness can be achieved using this process. In addition to the above, granulation can be used to combine (or mix) several ingredients, where each granule is a combination of several ingredients such as an API (active pharmaceutical ingredient), excipient, binder, disintegrant and lubricant.

Types of Wet Granulation:

The most common type of granulator used in the pharmaceutical industry today is a wet granulation which is available in both a high shear and low shear design. The high shear mixers are the more intense cousins of mixer technology while the low shear process utilizes fluidized bed technology.

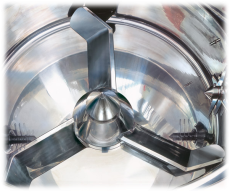

The most common type of granulator used in the pharmaceutical industry today is a wet granulation which is available in both a high shear and low shear design. The high shear mixers are the more intense cousins of mixer technology while the low shear process utilizes fluidized bed technology.  A typical high shear granulator is shown to the right, consisting of a main impeller on the bottom of the processing chamber and a chopper located higher up in the chamber.

A typical high shear granulator is shown to the right, consisting of a main impeller on the bottom of the processing chamber and a chopper located higher up in the chamber.

The main drive shaft can enter through the top (see photo on left) or bottom of the processing chamber but in both cases the impeller imparts shear energy by moving the product along the floor and walls of the chamber. The chopper sits above the process in a less dense zone, protruding out from the process chamber wall or roof, where it prevents agglomerates from building by returning the material back into the rotating bed of material. Binder liquid is introduced through the roof of the processing chamber, using a hydraulic nozzle or a simple fitting, and the liquid is uniformly distributed into the product mass due to the shear forces present.

Top-driven granulators are considered easier to clean since the impeller blade lifts out of the chamber and the seal is above the rotating mass. Bottom-driven granulators typically have tighter tolerances between the impeller blade and processing changers walls and floor thereby providing higher shear but the shaft seal sits in the material.  Fluid beds granulators operate in a low or no shear environment. The material to be processed sits on a screen at the bottom of a cylindrical processing chamber and air is drawn up thought the bed of material.

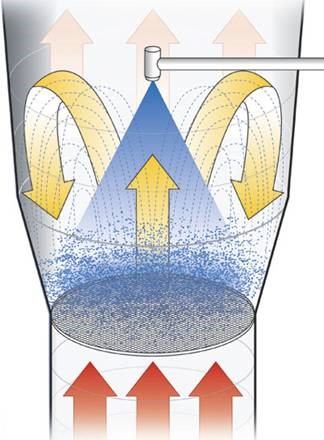

Fluid beds granulators operate in a low or no shear environment. The material to be processed sits on a screen at the bottom of a cylindrical processing chamber and air is drawn up thought the bed of material.

The air (red arrows in schematic to the left) entrains the particles (yellow articles) , lifting up in to the expansion chamber, thus causing the particles to be fluidized. Binder liquid (blue area) is introduced into the processing chamber via a high pressure nozzle using atomization air to create fine droplets the atomized binder droplets make contact the powder particles as they are suspended in air with no mechanical force present. As these droplets contact the suspended particles, the particles are bound  together forming groups of individual particles into granules. As the particles are entrained in the airstream, rise and then fall back to the bottom of the processing chamber they constantly pass through the droplet cloud, thereby building larger granules.

together forming groups of individual particles into granules. As the particles are entrained in the airstream, rise and then fall back to the bottom of the processing chamber they constantly pass through the droplet cloud, thereby building larger granules.

A filter system above the processing zone ensures that any fines or dust particles are trapped and returned to the process, ensuring high yields with minimum product loss. Fluid bed granulation offer tremendous flexibility since the particle size can be readily controlled by varying key process parameters such as spray rate, droplet size, particle recirculation rate, air volume and air temperature among others. In addition, once binder addition is complete and the product has been fully granulated the product is then dried in the same process chamber by the heated fluidizing air, thus offering a so-called “single pot process” as compared to high shear granulators.

Advantages and Limitations:

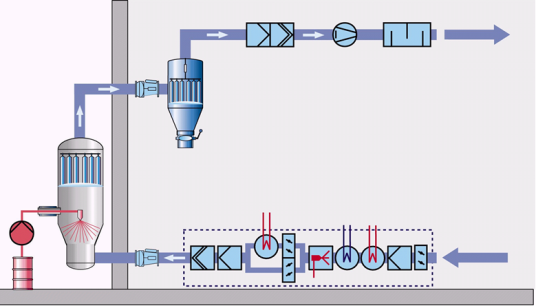

High shear granulators produce dense granules and have relatively short batch times. The process is very well understood and the equipment itself does not have any special height or installation requirements, but a separate drying process is required which means either a fluid bed dryer or a tray dryer, with all of their additional space and support requirements.  The fluid bed processors produce a porous granule, have high yields and are physically much taller and require space for ancillary components such as air preconditioning units, fans and after- filters (see schematic at right).

The fluid bed processors produce a porous granule, have high yields and are physically much taller and require space for ancillary components such as air preconditioning units, fans and after- filters (see schematic at right).

Spray rates are constrained by the fluidized bed thermodynamics which, in combination with the post-spraying drying phase, require longer batch times than the high shear process.  Mechanically, each system has pros and cons. Top drive systems shaft length from support bearing to blade are longer, creating mechanical issues, although the seal is kept away from the product bed.

Mechanically, each system has pros and cons. Top drive systems shaft length from support bearing to blade are longer, creating mechanical issues, although the seal is kept away from the product bed.

The bottom drive requires a sophisticated seal along the main blade shaft. Historically, the bottom drive systems have had tighter blade-to-chamber tolerances since the top drive systems have to be moved into position, requiring more forgiving clearances, but current engineering and machining practices have made the choice between these two approaches less critical.

Design Considerations:

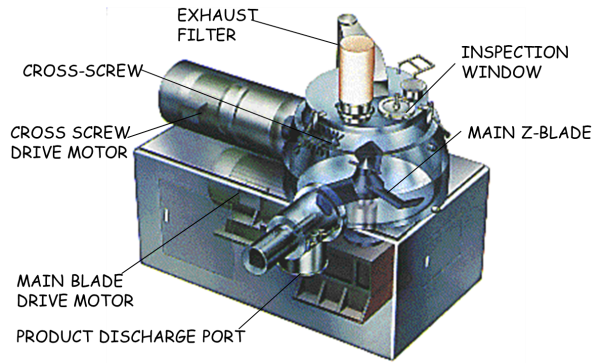

High Shear Granulators produce a wet mass once the process is complete; it is typically discharged through a wet mill to break up any agglomerates (i.e., oversize granules) and facilitate downstream drying, most often done in a fluid bed dryer. The discharge of a bottom-drive high shear granulator is noted in the schematic on the right.

High Shear Granulators produce a wet mass once the process is complete; it is typically discharged through a wet mill to break up any agglomerates (i.e., oversize granules) and facilitate downstream drying, most often done in a fluid bed dryer. The discharge of a bottom-drive high shear granulator is noted in the schematic on the right.

The mill can be close-coupled but it impacts the geometry of the integrated high  shear/fluid bed dryer system process train since certain angles must be maintained to ensure that product flows easily from the granualtor to the mill and then into the dryer. Top drive versions have additional layout considerations since the motors for both the main blade and chopper in a housing mounted above the processing chamber. In these machines, either the processing chamber or motor housing must move into position after the product charge is loaded.

shear/fluid bed dryer system process train since certain angles must be maintained to ensure that product flows easily from the granualtor to the mill and then into the dryer. Top drive versions have additional layout considerations since the motors for both the main blade and chopper in a housing mounted above the processing chamber. In these machines, either the processing chamber or motor housing must move into position after the product charge is loaded.

Fluid bed granulators offer what can be a dizzying array of possibilities for both feeding raw materials and discharging finished product. Material can be conveyed in using pneumatic transport or vacuum  conveying via an entrance port on the expansion chamber or it can be gravity fed from the floor above or a mezzanine. Granulated product can be discharged manually with a simple trolley-mounted product container or in a more enclosed, automated fashionably rotating the bottom screen that holds the product bed or via a side using bottom discharge port situation just above the bottom screen.

conveying via an entrance port on the expansion chamber or it can be gravity fed from the floor above or a mezzanine. Granulated product can be discharged manually with a simple trolley-mounted product container or in a more enclosed, automated fashionably rotating the bottom screen that holds the product bed or via a side using bottom discharge port situation just above the bottom screen.

There are several variations on each of these basic principles which, when coupled with options for in line milling on both the feed and discharge elements, result in an almost overwhelming number of combinations. The design and related implication are beyond the scope of this knowledge brief but are mentioned here as a topic for further consideration.

Finally, the combination of a high shear granulator with a fluid bed dryer combines the various options above, often in a highly space efficient manner. In addition, the close coupling often allows more integration before the system leaves the factory, providing less work on site for both installation and commissioning.

Learn more about Oral Solid Dosage (OSD) processes by attending a training course in April in Manhattan Beach, CA. The Oral Solid Dosage Forms: Understanding the Unit Operations, Process, Equipment and Technology for OSD Manufacturing course will emphasize the process, equipment and technology associated with unit operation, give you a general understanding of the OSD process and a case study of production related issues and concerns.